Is C# a low-level language?

01 Mar 2019 - 3535 wordsI’m a massive fan of everything Fabien Sanglard does, I love his blog and I’ve read both his books cover-to-cover (for more info on his books, check out the recent Hansleminutes podcast).

Recently he wrote an excellent post where he deciphered a postcard sized raytracer, un-packing the obfuscated code and providing a fantastic explanation of the maths involved. I really recommend you take the time to read it!

But it got me thinking, would it be possible to port that C++ code to C#?

Partly because in my day job I’ve been having to write a fair amount of C++ recently and I’ve realised I’m a bit rusty, so I thought this might help!

But more significantly, I wanted to get a better insight into the question is C# a low-level language?

A slightly different, but related question is how suitable is C# for ‘systems programming’? For more on that I really recommend Joe Duffy’s excellent post from 2013.

Line-by-line port

I started by simply porting the un-obfuscated C++ code line-by-line to C#. Turns out that this was pretty straight forward, I guess the story about C# being C++++ is true after all!!

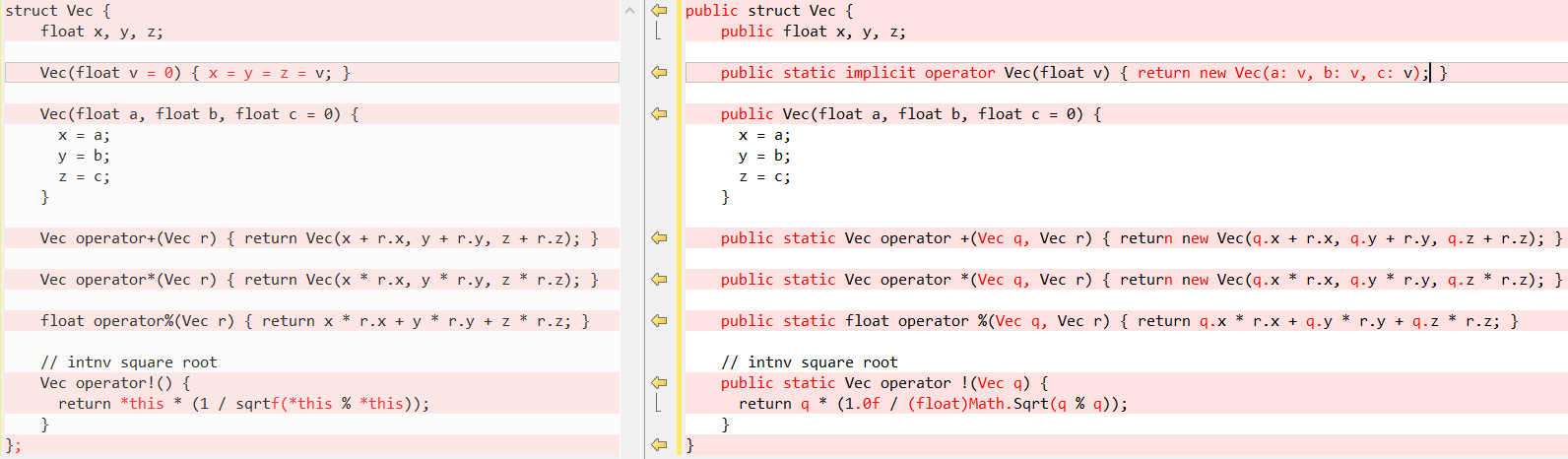

Let’s look at an example, the main data structure in the code is a ‘vector’, here’s the code side-by-side, C++ on the left and C# on the right:

So there’s a few syntax differences, but because .NET lets you define your own ‘Value Types’ I was able to get the same functionality. This is significant because treating the ‘vector’ as a struct means we can get better ‘data locality’ and the .NET Garbage Collector (GC) doesn’t need to be involved as the data will go onto the stack (probably, yes I know it’s an implementation detail).

For more info on structs or ‘value types’ in .NET see:

- Heap vs stack, value type vs reference type

- Value Types vs Reference Types

- Memory in .NET - what goes where

- The Truth About Value Types

- The Stack Is An Implementation Detail, Part One

In particular that last post form Eric Lippert contains this helpful quote that makes it clear what ‘value types’ really are:

Surely the most relevant fact about value types is not the implementation detail of how they are allocated, but rather the by-design semantic meaning of “value type”, namely that they are always copied “by value”. If the relevant thing was their allocation details then we’d have called them “heap types” and “stack types”. But that’s not relevant most of the time. Most of the time the relevant thing is their copying and identity semantics.

Now lets look at how some other methods look side-by-side (again C++ on the left, C# on the right), first up RayTracing(..):

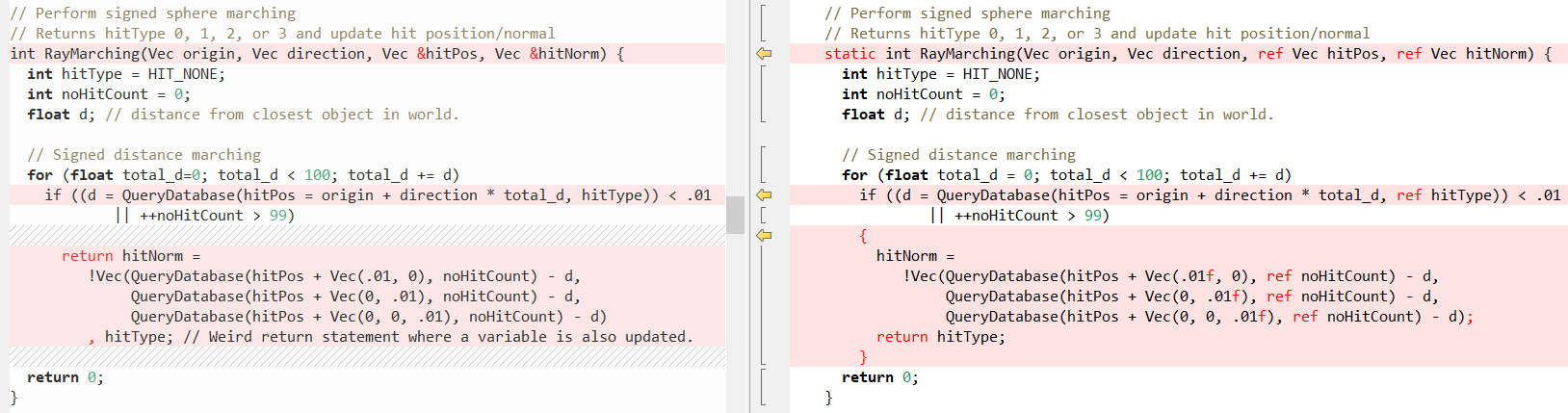

Next QueryDatabase(..):

(see Fabien’s post for an explanation of what these 2 functions are doing)

But the point is that again, C# lets us very easily write C++ code! In this case what helps us out the most is the ref keyword which lets us pass a value by reference. We’ve been able to use ref in method calls for quite a while, but recently there’s been a effort to allow ref in more places:

Now sometimes using ref can provide a performance boost because it means that the struct doesn’t need to be copied, see the benchmarks in Adam Sitniks post and Performance traps of ref locals and ref returns in C# for more information.

However what’s most important for this scenario is that it allows us to have the same behaviour in our C# port as the original C++ code. Although I want to point out that ‘Managed References’ as they’re known aren’t exactly the same as ‘pointers’, most notably you can’t do arithmetic on them, for more on this see:

Performance

So, it’s all well and good being able to port the code, but ultimately the performance also matters. Especially in something like a ‘ray tracer’ that can take minutes to run! The C++ code contains a variable called sampleCount that controls the final quality of the image, with sampleCount = 2 it looks like this:

Which clearly isn’t that realistic!

However once you get to sampleCount = 2048 things look a lot better:

But, running with sampleCount = 2048 means the rendering takes a long time, so all the following results were run with it set to 2, which means the test runs completed in ~1 minute. Changing sampleCount only affects the number of iterations of the outermost loop of the code, see this gist for an explanation.

Results after a ‘naive’ line-by-line port

To be able to give a meaningful side-by-side comparison of the C++ and C# versions I used the time-windows tool that’s a port of the Unix time command. My initial results looked this this:

| C++ (VS 2017) | .NET Framework (4.7.2) | .NET Core (2.2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elapsed time (secs) | 47.40 | 80.14 | 78.02 |

| Kernel time | 0.14 (0.3%) | 0.72 (0.9%) | 0.63 (0.8%) |

| User time | 43.86 (92.5%) | 73.06 (91.2%) | 70.66 (90.6%) |

| page fault # | 1,143 | 4,818 | 5,945 |

| Working set (KB) | 4,232 | 13,624 | 17,052 |

| Paged pool (KB) | 95 | 172 | 154 |

| Non-paged pool | 7 | 14 | 16 |

| Page file size (KB) | 1,460 | 10,936 | 11,024 |

So initially we see that the C# code is quite a bit slower than the C++ version, but it does get better (see below).

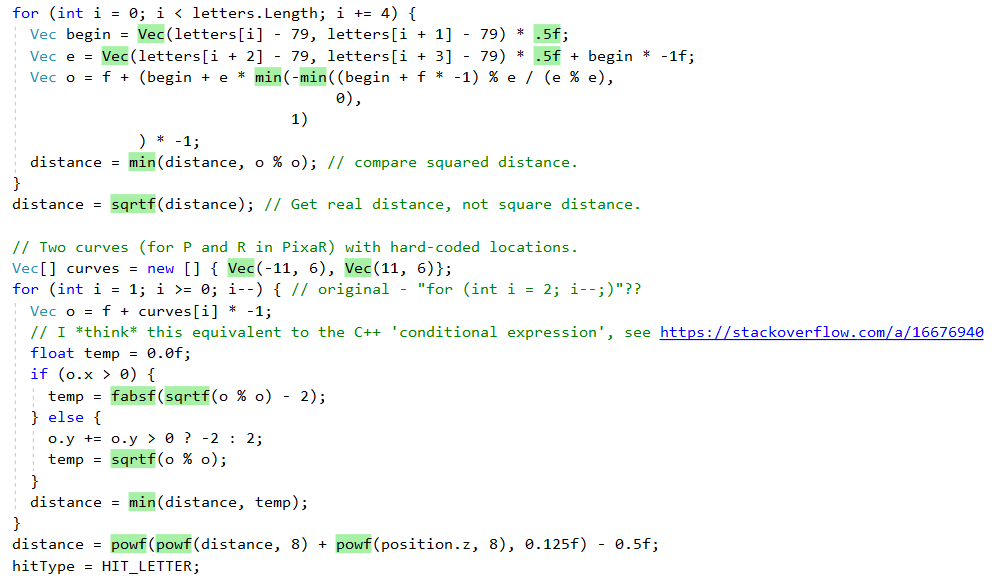

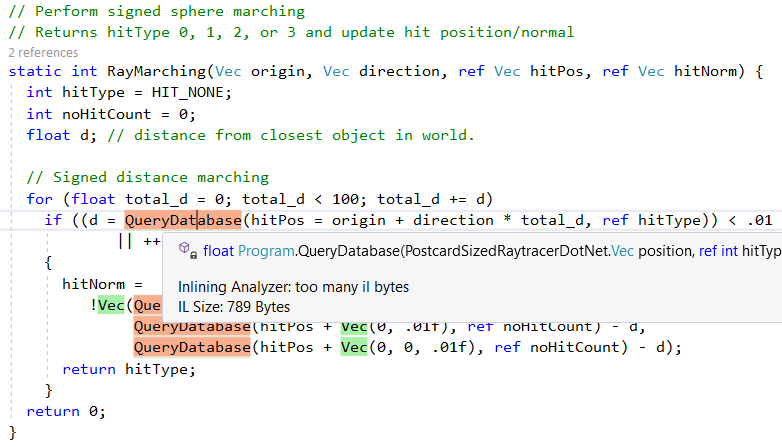

However lets first look at what the .NET JIT is doing for us even with this ‘naive’ line-by-line port. Firstly, it’s doing a nice job of in-lining the smaller ‘helper methods’, we can see this by looking at the output of the brilliant Inlining Analyzer tool (green overlay = inlined):

However, it doesn’t inline all methods, for example QueryDatabase(..) is skipped because of it’s complexity:

Another feature that the .NET Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler provides is converting specific methods calls into corresponding CPU instructions. We can see this in action with the sqrt wrapper function, here’s the original C# code (note the call to Math.Sqrt):

// intnv square root

public static Vec operator !(Vec q) {

return q * (1.0f / (float)Math.Sqrt(q % q));

}

And here’s the assembly code that the .NET JIT generates, there’s no call to Math.Sqrt and it makes use of the vsqrtsd CPU instruction:

; Assembly listing for method Program:sqrtf(float):float

; Emitting BLENDED_CODE for X64 CPU with AVX - Windows

; Tier-1 compilation

; optimized code

; rsp based frame

; partially interruptible

; Final local variable assignments

;

; V00 arg0 [V00,T00] ( 3, 3 ) float -> mm0

;# V01 OutArgs [V01 ] ( 1, 1 ) lclBlk ( 0) [rsp+0x00] "OutgoingArgSpace"

;

; Lcl frame size = 0

G_M8216_IG01:

vzeroupper

G_M8216_IG02:

vcvtss2sd xmm0, xmm0

vsqrtsd xmm0, xmm0

vcvtsd2ss xmm0, xmm0

G_M8216_IG03:

ret

; Total bytes of code 16, prolog size 3 for method Program:sqrtf(float):float

; ============================================================

(to get this output you need to following these instructions, use the ‘Disasmo’ VS2019 Add-in or take a look at SharpLab.io)

These replacements are also known as ‘intrinsics’ and we can see the JIT generating them in the code below. This snippet just shows the mapping for AMD64, the JIT also targets X86, ARM and ARM64, the full method is here

bool Compiler::IsTargetIntrinsic(CorInfoIntrinsics intrinsicId)

{

#if defined(_TARGET_AMD64_) || (defined(_TARGET_X86_) && !defined(LEGACY_BACKEND))

switch (intrinsicId)

{

// AMD64/x86 has SSE2 instructions to directly compute sqrt/abs and SSE4.1

// instructions to directly compute round/ceiling/floor.

//

// TODO: Because the x86 backend only targets SSE for floating-point code,

// it does not treat Sine, Cosine, or Round as intrinsics (JIT32

// implemented those intrinsics as x87 instructions). If this poses

// a CQ problem, it may be necessary to change the implementation of

// the helper calls to decrease call overhead or switch back to the

// x87 instructions. This is tracked by #7097.

case CORINFO_INTRINSIC_Sqrt:

case CORINFO_INTRINSIC_Abs:

return true;

case CORINFO_INTRINSIC_Round:

case CORINFO_INTRINSIC_Ceiling:

case CORINFO_INTRINSIC_Floor:

return compSupports(InstructionSet_SSE41);

default:

return false;

}

...

}

As you can see, some methods are implemented like this, e.g. Sqrt and Abs, but for others the CLR instead uses the C++ runtime functions for instance powf.

This entire process is explained very nicely in How is Math.Pow() implemented in .NET Framework?, but we can also see it in action in the CoreCLR source:

COMSingle::Powimplementation, i.e. the method that’s executed if you callMathF.Pow(..)from C# code- Mapping to C runtime method implementations

- Cross-platform version of

powfimplementation that ensures the same behaviour across OSes

Results after simple performance improvements

However, I wanted to see if my ‘naive’ line-by-line port could be improved, after some profiling I made two main changes:

- Remove in-line array initialisation

- Switch from

Math.XXX(..)functions to theMathF.XXX()counterparts.

These changes are explained in more depth below

Remove in-line array initialisation

For more information about why this is necessary see this excellent Stack Overflow answer from Andrey Akinshin complete with benchmarks and assembly code! It comes to the following conclusion:

Conclusion

- Does .NET caches hardcoded local arrays? Kind of: the Roslyn compiler put it in the metadata.

- Do we have any overhead in this case? Unfortunately, yes: JIT will copy the array content from the metadata for each invocation; it will work longer than the case with a static array. Runtime also allocates objects and produce memory traffic.

- Should we care about it? It depends. If it’s a hot method and you want to achieve a good level of performance, you should use a static array. If it’s a cold method which doesn’t affect the application performance, you probably should write “good” source code and put the array in the method scope.

You can see the change I made in this diff.

Using MathF functions instead of Math

Secondly and most significantly I got a big perf improvement by making the following changes:

#if NETSTANDARD2_1 || NETCOREAPP2_0 || NETCOREAPP2_1 || NETCOREAPP2_2 || NETCOREAPP3_0

// intnv square root

public static Vec operator !(Vec q) {

return q * (1.0f / MathF.Sqrt(q % q));

}

#else

public static Vec operator !(Vec q) {

return q * (1.0f / (float)Math.Sqrt(q % q));

}

#endif

As of ‘.NET Standard 2.1’ there are now specific float implementations of the common maths functions, located in the System.MathF class. For more information on this API and it’s implementation see:

- New API for single-precision math

- Adding single-precision math functions

- Provide a set of unit tests over the new single-precision math APIs

- System.Math and System.MathF should be implemented in managed code, rather than as FCALLs to the C runtime

- Moving

Math.Abs(double)andMath.Abs(float)to be implemented in managed code. - Design and process for adding platform dependent intrinsics to .NET

After these changes, the C# code is ~10% slower than the C++ version:

| C++ (VS C++ 2017) | .NET Framework (4.7.2) | .NET Core (2.2) TC OFF | .NET Core (2.2) TC ON | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elapsed time (secs) | 41.38 | 58.89 | 46.04 | 44.33 |

| Kernel time | 0.05 (0.1%) | 0.06 (0.1%) | 0.14 (0.3%) | 0.13 (0.3%) |

| User time | 41.19 (99.5%) | 58.34 (99.1%) | 44.72 (97.1%) | 44.03 (99.3%) |

| page fault # | 1,119 | 4,749 | 5,776 | 5,661 |

| Working set (KB) | 4,136 | 13,440 | 16,788 | 16,652 |

| Paged pool (KB) | 89 | 172 | 150 | 150 |

| Non-paged pool | 7 | 13 | 16 | 16 |

| Page file size (KB) | 1,428 | 10,904 | 10,960 | 11,044 |

TC = Tiered Compilation (I believe that it’ll be on by default in .NET Core 3.0)

For completeness, here’s the results across several runs:

| Run | C++ (VS C++ 2017) | .NET Framework (4.7.2) | .NET Core (2.2) TC OFF | .NET Core (2.2) TC ON |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TestRun-01 | 41.38 | 58.89 | 46.04 | 44.33 |

| TestRun-02 | 41.19 | 57.65 | 46.23 | 45.96 |

| TestRun-03 | 42.17 | 62.64 | 46.22 | 48.73 |

Note: the difference between .NET Core and .NET Framework is due to the lack of the MathF API in .NET Framework v4.7.2, for more info see Support .Net Framework (4.8?) for netstandard 2.1.

Further performance improvements

However I’m sure that others can do better!

If you’re interested in trying to close the gap the C# code is available. For comparison, you can see the assembly produced by the C++ compiler courtesy of the brilliant Compiler Explorer.

Finally, if it helps, here’s the output from the Visual Studio Profiler showing the ‘hot path’ (after the perf improvement described above):

Is C# a low-level language?

Or more specifically:

What language features of C#/F#/VB.NET or BCL/Runtime functionality enable ‘low-level’* programming?

* yes, I know ‘low-level’ is a subjective term 😊

Note: Any C# developer is going to have a different idea of what ‘low-level’ means, these features would be taken for granted by C++ or Rust programmers.

Here’s the list that I came up with:

- ref returns and ref locals

- “tl;dr Pass and return by reference to avoid large struct copying. It’s type and memory safe. It can be even faster than

unsafe!”

- “tl;dr Pass and return by reference to avoid large struct copying. It’s type and memory safe. It can be even faster than

- Unsafe code in .NET

- “The core C# language, as defined in the preceding chapters, differs notably from C and C++ in its omission of pointers as a data type. Instead, C# provides references and the ability to create objects that are managed by a garbage collector. This design, coupled with other features, makes C# a much safer language than C or C++.”

- Managed pointers in .NET

- “There is, however, another pointer type in CLR – a managed pointer. It could be defined as a more general type of reference, which may point to other locations than just the beginning of an object.”

- C# 7 Series, Part 10: Span<T> and universal memory management

- “

System.Span<T>is a stack-only type (ref struct) that wraps all memory access patterns, it is the type for universal contiguous memory access. You can think the implementation of the Spancontains a dummy reference and a length, accepting all 3 memory access types."

- “

- Interoperability (C# Programming Guide)

- “The .NET Framework enables interoperability with unmanaged code through platform invoke services, the

System.Runtime.InteropServicesnamespace, C++ interoperability, and COM interoperability (COM interop).”

- “The .NET Framework enables interoperability with unmanaged code through platform invoke services, the

However, I know my limitations and so I asked on twitter and got a lot more replies to add to the list:

- Ben Adams “Platform intrinsics (CPU instruction access)”

- Marc Gravell “SIMD via Vector

(which mixes well with Span ) is *fairly* low; .NET Core should (soon?) offer direct CPU intrinsics for more explicit usage targeting particular CPU ops" - Marc Gravell “powerful JIT: things like range elision on arrays/spans, and the JIT using per-struct-T rules to remove huge chunks of code that it knows can’t be reached for that T, or on your particular CPU (BitConverter.IsLittleEndian, Vector.IsHardwareAccelerated, etc)”

- Kevin Jones “I would give a special shout-out to the

MemoryMarshalandUnsafeclasses, and probably a few other things in theSystem.Runtime.CompilerServicesnamespace.” - Theodoros Chatzigiannakis “You could also include

__makerefand the rest.” - damageboy “Being able to dynamically generate code that fits the expected input exactly, given that the latter will only be known at runtime, and might change periodically?”

- Robert Haken “dynamic IL emission”

- Victor Baybekov “Stackalloc was not mentioned. Also ability to write raw IL (not dynamic, so save on a delegate call), e.g. to use cached

ldftnand call them viacalli. VS2017 has a proj template that makes this trivial via extern methods + MethodImplOptions.ForwardRef + ilasm.exe rewrite.” - Victor Baybekov “Also MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining “does enable ‘low-level’ programming” in a sense that it allows to write high-level code with many small methods and still control JIT behavior to get optimized result. Otherwise uncomposable 100s LOCs methods with copy-paste…”

- Ben Adams “Using the same calling conventions (ABI) as the underlying platform and p/invokes for interop might be more of a thing though?”

- Victor Baybekov “Also since you mentioned #fsharp - it does have

inlinekeyword that does the job at IL level before JIT, so it was deemed important at the language level. C# lacks this (so far) for lambdas which are always virtual calls and workarounds are often weird (constrained generics).” - Alexandre Mutel “new SIMD intrinsics, Unsafe Utility class/IL post processing (e.g custom, Fody…etc.). For C#8.0, upcoming function pointers…”

- Alexandre Mutel “related to IL, F# has support for direct IL within the language for example”

- OmariO “BinaryPrimitives. Low-level but safe.” (https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/api/system.buffers.binary.binaryprimitives?view=netcore-3.0)

- Kouji (Kozy) Matsui “How about native inline assembler? It’s difficult for how relation both toolchains and runtime, but can replace current P/Invoke solution and do inlining if we have it.”

- Frank A. Krueger “Ldobj, stobj, initobj, initblk, cpyblk.”

- Konrad Kokosa “Maybe Thread Local Storage? Fixed Size Buffers? unmanaged constraint and blittable types should be probably mentioned:)”

- Sebastiano Mandalà “Just my two cents as everything has been said: what about something as simple as struct layout and how padding and memory alignment and order of the fields may affect the cache line performance? It’s something I have to investigate myself too”

- Nino Floris “Constants embedding via readonlyspan, stackalloc, finalizers, WeakReference, open delegates, MethodImplOptions, MemoryBarriers, TypedReference, varargs, SIMD, Unsafe.AsRef can coerce struct types if layout matches exactly (used for a.o. TaskAwaiter and its

version)"

So in summary, I would say that C# certainly lets you write code that looks a lot like C++ and in conjunction with the Runtime and Base-Class Libraries it gives you a lot of low-level functionality

Discuss this post on Hacker News, /r/programming, /r/dotnet or /r/csharp

Further Reading

- Patterns for high-performance C#. by Federico Andres Lois

- Performance Quiz #6 — Chinese/English Dictionary reader (From 2005, 2 Microsoft bloggers have a ‘performance’ battle, C++ v. C#)

- Performance Quiz #6 — Conclusion, Studying the Space

- How much faster is C++ than C#?

- Optimizing managed C# vs. native C++ code (2005)

The Unity ‘Burst’ Compiler:

.png)

%20-%20Report20190221-2029-After-MathF-Changes-NetCore.png)